Vcan-HPV: Japanese medical students inform young people about HPV

Let’s PreVent CANcer

Dr. Joel Palefsky, Principal Investigator of the ANCHOR study (Anal Cancer HSIL2 Outcomes Research), is one of the most knowledgeable medical experts in the world when it comes to talking about HPV and anal cancer. Since today is Anal Cancer Awareness Day, we caught up with him to get a few of his insights about this specific type of HPV cancer.

Q: Dr. Palefsky, do we really need another awareness day just for anal cancer?

Yes, I think we do. About 80% of all sexually active people will get HPV in their anogenital tract at some point in their lives. We’re all in this together and we need to talk about it- it can save your life or the life of someone you care about.

Q: How prevalent is anal cancer anyway? Isn’t it rare?

An estimated 51.000 cases of anal cancer are diagnosed each year world-wide1 with more women affected than men. That’s a lot of people, but yes, anal cancer is still a relatively rare cancer among the general population.

However addressing anal cancer is still important for several reasons: First, it is unacceptably common in certain risk groups which I will tell you about in a minute. Second, even in the general population, the incidence of anal cancer has been increasing since the 1970s, and in some groups in the U.S., such as white women over the age of 65 years, anal cancer is more common than cervical cancer. Third, like cervical cancer, we have the tools to greatly reduce the incidence of anal cancer - human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination for younger people, and screening and treatment of anal cancer precursors for older people. Most people don’t know about anal cancer. Lack of public awareness about a disease we have the tools to prevent in many cases make having a day devoted to awareness of anal cancer especially important.

Q: What causes anal cancer? Who is at risk to get it? What can be done to prevent it?

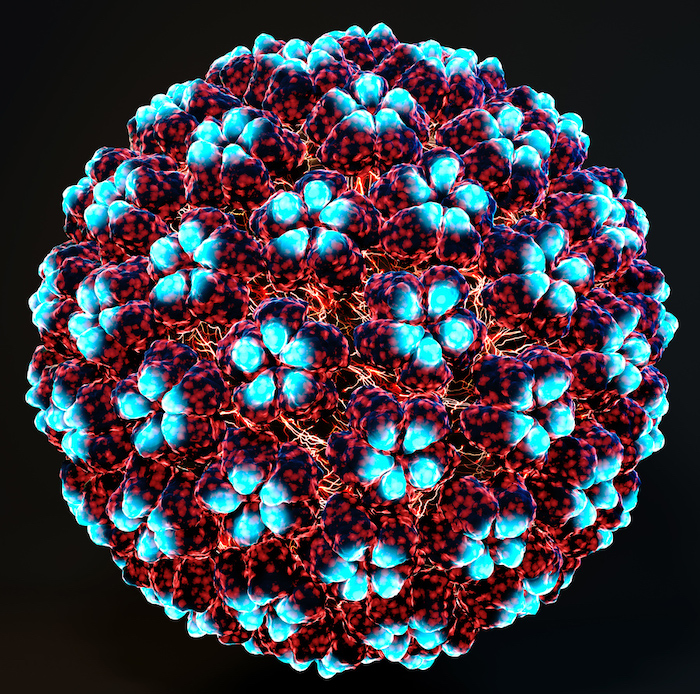

HPV infection is the most important risk factor for anal cancer. About 90% of anal cancers are caused by HPV. Anal cancer is caused by the same HPV types as those that cause cervical cancer. Other risk factors for anal cancer in addition to anal HPV infection include being immunocompromised, having HPV infection at other locations in the anogenital tract, smoking, and chronic irritation due to fissures and fistulas. Most people who have anal HPV infection don’t develop any problems, but a small proportion of people may develop anal cancer precursors and even smaller proportion may develop anal cancer. People who are immunocompromised due to HIV or other causes are at the highest risk of developing anal cancer.

Anal cancer prevention is based on the same pillars of prevention as cervical cancer. These include HPV vaccination to prevent initial anal HPV infection before a person has been exposed to the HPV types in the vaccine. HPV vaccination is only preventive and doesn’t help if a person has already been exposed to a given HPV type. So the ideal time to vaccinate boys and girls is before initiation of sexual activity, e.g., the 9–12-year age group. Vaccination is also recommended up to age 26 years.

The second tier is called secondary prevention. Here clinicians look for anal cancer precursors called high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL), using a technique called high resolution anoscopy (HRA). The idea is to treat the HSIL before it progresses to anal cancer. This is similar to how cervical cancer is prevented when a woman with an abnormal cervical Pap test or a positive cervical HPV test is referred for colposcopy. If a cervical HSIL is found at colposcopy, then that cervical lesion is removed to reduce the risk of progression to cervical cancer.

Q: Dr. Palefsky, you’ve been leading major research (the ANCHOR Study) on treating anal cancer precursor lesions to reduce the risk of cancer. Several months ago it was announced the national clinical trial in the US was halted. Is that good news or bad?

It is good news- the study showed that treating anal HSIL can reduce the risk of progression to anal cancer, just like treating cervical HSIL is known to reduce the risk of progression to cervical cancer.

Q: The ANCHOR study focused on people who are HIV positive. Why? Are the results still relevant to the wider population?

We think the results are relevant because people living with HIV (PLWH) are probably the toughest group of all to treat. HSIL lesions in PLWH can be large and numerous, and often come back after treatment. Despite these challenges, the ANCHOR Study still showed that treating anal HSIL can reduce the risk of anal cancer. Our thinking is that if we can succeed with PLWH, our results may be as good or even better among groups that are less challenging such as the other groups mentioned above who are at higher risk of anal cancer than the general population.

Q: Is anal cancer screening now viable for the general population? How far are we away from that?

It’s important to understand that we probably don’t need to screen the general population given how rare anal cancer is in this group. Instead, we will probably want to screen the more vulnerable groups mentioned above that are known to be at increased risk of anal cancer. In these groups, we are still a little way off from routine screening. First, the results of the ANCHOR Study need to be reviewed, along with other data such as impact of treating lesions on quality of life. Cost-benefit analyses need to be considered for incorporation into standard of care guidelines. We need to define the best way to screen people and to find ways to determine which people with anal HSIL need immediate treatment versus those who can be safely followed without treatment. Finally, we need to substantially ramp up training programs to increase the number of healthcare professionals who are trained in HRA.

Q: Why do you think it’s important to make people feel more comfortable discussing HPV and anal cancer?

As I mentioned at the beginning, we’re all in this together. We need to talk about HPV because it is the most common sexually transmitted infection. Most sexually active people will get at least one HPV type in their anogenital tract at some point in their lives. Talking about HPV helps to reduce the stigma around having HPV in the anus or any other part of the anogenital tract. We also need to reduce the stigma about anal cancer. We have the tools to prevent this disease- now we need to reduce stigma that could prevent someone from seeking potentially lifesaving anal cancer prevention or treatment services.

Here is what American actress and HPV awareness advocate Marcia Cross, herself a ‘thriver’ after battling anal cancer, had to say about reducing the stigma of HPV during the live panel event on March 4th, 2022, International HPV Awareness Day (click here to watch the full event).

For more information on Anal Cancer visit USFC Anal Cancer Foundation website: http://analcancerinfo.ucsf.edu

1The Anus Factsheet, Global Cancer Observatory 2020

2HSIL: high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions

Find out more about:

Let’s PreVent CANcer

Teenage girl striving to prevent cervical cancer in her country

Innovative way to raise awareness about cervical cancer in Jordan