Vcan-HPV: Japanese medical students inform young people about HPV

Let’s PreVent CANcer

Dr. Jessica Wells, (PhD, RN, WHNP-BC, FAAN) is assistant professor at Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. She is also an active member of the IPVS Campaign Committee, which coordinates the International HPV Awareness Day Campaign. When Jessica mentioned that she is related to Henrietta Lacks, we wanted to explore the impact, inspiration and legacy of Henrietta Lacks in relation to understanding and preventing HPV and related cancer.

Dr. Jessica Wells, (PhD, RN, WHNP-BC, FAAN) is assistant professor at Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. She is also an active member of the IPVS Campaign Committee, which coordinates the International HPV Awareness Day Campaign. When Jessica mentioned that she is related to Henrietta Lacks, we wanted to explore the impact, inspiration and legacy of Henrietta Lacks in relation to understanding and preventing HPV and related cancer.

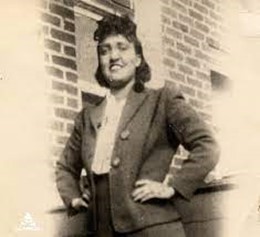

If Henrietta Lacks was still alive, August 1st would have been her 102nd birthday. Sadly, Henrietta died of cervical cancer at just 31 years of age, leaving five children to grow up without their mother. During her cancer treatment at John Hopkins in 1951, cervical cells were taken for study without her consent, which was standard practice with patients at that time. Dr. George Gey discovered that Henrietta's cancerous cervical cells were immortal. Unlike normal human cells, immortal cells mutate in a way that allows them to continue multiplying for a prolonged period of time in vitro (in a Petrie dish). Known by scientists as “He-La” — this remarkably durable and prolific line of cells has been used in scientific research on the effects of zero gravity in outer space, the development of polio and COVID-19 vaccines, the study of leukemia, the AIDS virus and cancer worldwide. 1

Q: Jessica, how are you related to Henrietta Lacks?

JW: My great grandmother (on my mother’s side) and Henrietta Lacks were sisters. My mother was Henrietta’s great-niece. That makes me Henrietta’s great, great niece.

Q: Did you hear about Henrietta while you were growing up?

JW: (laughing) No, as a kid I wasn’t really aware of the family connection or her significance. My mother grew up in the small rural town of Clover, Virginia, where much of the family comes from. She used to share family stories and Henrietta’s name would get mentioned in passing. When I was in high school, we made a trip to the Clover area to place a tombstone on my grandmother’s grave. I remember that it was a hot, muggy day as we ventured deep into the woods to the family grave site. While searching for my grandmother’s grave marker, my mother pointed to a tombstone some distance away and said, “Oh, that’s where Aunt Henrietta is buried. Some scientists wanted to exhume her body, but we told them ‘No.’” Being a teenager at the time, I didn’t think much of it. Years later when I was in grad school, my mother called to tell me someone was writing a book about our family. “What about our family?” I asked. She explained our relation to Henrietta, but it wasn’t until the book2 actually came out and I received a copy of it that all of the pieces together and understood how important she was. Thumbing through the book and seeing pictures of my own family was strange, in a good way. He-La cells have been used to advance medical science for the last seventy years, it’s amazing.

Q: Henrietta’s inadvertent contribution to the advancement of medical science has been enormous. How do you think she would feel if she knew all the ways in which He-La cells have benefited our health?

JW: It’s difficult to say what Henrietta might have felt about her cells being used for things like the polio vaccine and other vaccines that have saved so many lives. I know my mother was proud of this family legacy, that her great aunt, from humble Clover, Virginia, has enabled the advancement of medical science on a global level - touching the lives of hundreds of millions of people - every generation since, and still today. Just last month I was part of a panel reviewing grant proposals for medical research projects, one of which was proposing to use He-La cells in the study. There she is again.

Q: How have He-La cells advanced prevention and treatment of HPV?

JW: In the early 2000s, the study of He-La cells helped scientists to prove that HPV causes cervical cancer. In 2008, German virologist Dr. Harald zur Hausen won the Nobel Prize in Medicine for discovering the two strains of HPV that caused cervical cancer. He-La cells are used to study the effects of toxins, drugs, hormones and viruses on the growth of cancer cells, all without experimenting on humans. Scientists used that knowledge to develop HPV vaccines which became available in 2006.

Q: As a black woman at the beginning of in the 1950s, Henrietta must have experienced some of the worst inequality in American society at that time. Looking at healthcare today, what do you think has improved for women of color since then?

JW: The way medical research is conducted has improved thanks to the establishment and application of global guidelines such as the Declaration of Helsinki - Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects, published by the World Medical Association in 1964, and later in the US through the National Research Act of 1974. Standards like these emerged after we took a hard look at the history of misconduct in the past and came to terms with the facts: certain vulnerable populations – women of color, indigenous groups, minorities and the disabled have been subject to experimentation in medical research and treatment.

Exploitation in medical research has paralleled the disparity in civil rights of vulnerable populations throughout our history. Up until 1965, hospitals in the US were not penalized for discriminating on the basis of race. It wasn’t until Medicare funding could be withheld on the basis of racial discrimination that we saw desegregation in US hospitals. “Medicare ranks among the most important civil rights achievements in U.S. history’’.3

In terms of the history of gynecology in the US, it has been broadly acknowledged by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) that gynecological procedures were often practiced and perfected on female slaves back when slavery was commonplace.4 Thankfully, today medical research on human beings is governed by much stronger ethical principles than existed back in Henrietta’s day and earlier.

As for the quality of healthcare women of color receive in the US today, I don’t think there hasn’t been sufficient progress. Black women have the highest maternal mortality rate among the demographics we measure.5 They also have the highest cancer mortality rate.6 These disparities should be addressed.

Globally speaking, equal access to healthcare is often that much more difficult for women in many low-income countries around the world. Universal access to health care, without discrimination, is a human right. I remind my students of the WHO statement that “The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition.”7 There’s so much work still to be done.

Q: Do statistics show that women of color in the US are less inclined to vaccinate against HPV or to get screened than other groups?

JW: If a person belongs to a group that suffers from discrimination or unfair treatment by public authorities in one area of their lives (such as physical safety), the level of trust that they extend to all types of government officials usually declines. This affects their confidence in public health advice. If we then add misinformation about vaccine safety public and effectiveness spreading like wildfire on social media, people simply have a hard time filter fact from fiction and heeding sound advice meant to protect their well-being. Just look at how much push-back there has been with the COVID vaccine.

As for following advice on regular cervical screening, statistics show black women are less likely to be screened for cervical cancer thus more likely to diagnosed at more advanced stages for cervical cancer. The consequence is that black women are also more likely to die from cervical cancer.8

Q: What do you think still needs to happen regarding healthcare for women of color?

JW: These are turbulent times in terms of sexual and reproductive health of women in the US. Look at the recent Supreme Court ruling that overturned Roe v. Wade, the federal protection of the right to access abortion. Women’s reproductive rights and access to health services are now being decided by each state. Because of the correlation between women of color and relatively lower financial resources, these women will experience the impact of this decision more than women in other demographics because they can’t afford to travel to a state where abortion is legal. That’s a new reality.

There are so many layers to these issues, it’s like an onion. I believe that structural reform is needed to ensure equal access to quality reproductive health services (and related social services) for all women. It starts with making it easier for legal citizens to vote. It is quite aggravating that many states are legislating in the opposite direction, making it more difficult, inconvenient and time consuming to cast a vote. It’s a real battlefield for democracy.

Q: How do you think your great aunt Henrietta’s legacy fits into the meaning of the #BlackLivesMatter movement? What should it mean?

JW: Henrietta’s legacy fits symbolically into social justice movements like #BlackLivesMatter - she actually personifies black lives mattering. It’s not about mystifying her life; she was a young black woman who had the misfortune of developing and dying from cervical cancer in the 1950s. Her fate was tragic and unfortunately common. I imagine that Aunt Henrietta would be honored if her legacy were to inspire us all to push for social justice and equality for communities where it’s plain to see that it’s not happening – so that the benefits that society has gleaned from research using her cells are shared by all in equal measure. Not just in the US, but everywhere.

Back in Henrietta’s day, only a few exceptional people - statesmen, athletes, heroes of some kind, had a voice loud enough to be heard speaking up for equal civil rights. Today, as a black woman and women’s healthcare provider, I’ve experienced having to really assert myself in order to be heard in certain situations; in the hospital delivering my children, for example. I’ve had to advocate for myself, but what about those who cannot do that as easily?

Q: So, if Henrietta were still with us today, what would you like to say to her?

JW: The first thing I’d want to tell her is that thanks in part to He-La cells, we can prevent the cancer that took her life. We found out that a virus called HPV causes cervical cancer and now there is a safe, effective vaccine to prevent HPV. In combination with screening and treatment, we have the tools to eliminate cervical cancer within the next generation.9

I’d also want to tell her that our voices are getting louder and that women of color can be better heard now as we affect change. I think many people in this country feel very motivated to work hard on addressing these issues. We’re pulling up our sleeves and are ready to get to work.

1 https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/henriettalacks/importance-of-hela-cells.html

2 The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, by Rebecca Skloot (published February 2010)

3 Desegregation: The Hidden Legacy of Medicare, US News & World Report, Steven Sternberg July 29th, 2015

4 https://www.acog.org/-/media/project/acog/acogorg/files/pdfs/news/commitmentendracism-historyobgyn-022621-v11.pdf

5 https://www.cdc.gov/healthequity/features/maternal-mortality/index.html

6 American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2016. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2016:51.

7https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/health-is-a-fundamental-human-right

8 Racial disparities in cervical cancer: Worse than we thought, Heather J. Dalton MD, John H. Farley MD

9 WHO strategy for the elimination of cervical cancer, August 2020.

Teenage girl striving to prevent cervical cancer in her country

Innovative way to raise awareness about cervical cancer in Jordan